By the early 19th century, the long-standing relationship between the Church, Parish, and Parishioners had broken down. Agricultural reform, the Industrial Revolution, and population growth led to mass migration into new and existing urban centres, leading to a shortage of church places. In Manchester, for example, it is estimated that only 11,000 seats on church pews were available for a population of over 80,000 people.

The lack of churches caused moral panic about the absence of churches in the growing ‘godless’ suburbs. Some political commentators feared that without religious guidance, national life might descend into anarchy and revolution following the example of the recent French Revolution that had ended in 1799 In the early 19th century, the church and parish were normally the only providers of social welfare support, leaving many of these new, poor, urban populations with few provisions of any kind.

On 6 February 1818, at a public meeting in Freemasons Hall, a motion was carried to establish a church building society. Parliament was subsequently persuaded to allocate £1m (approximately £100m today) for church building projects. The new projects were to be overseen by a Commission with extensive new powers to rebuild old churches or to found new ones and to subdivide Parishes. Previously, such changes would normally have required an act of parliament. The Commissioners directed that the new church designs were to be robustly built, economical, have a tower or spire and be commissioned based on architectural competitions.

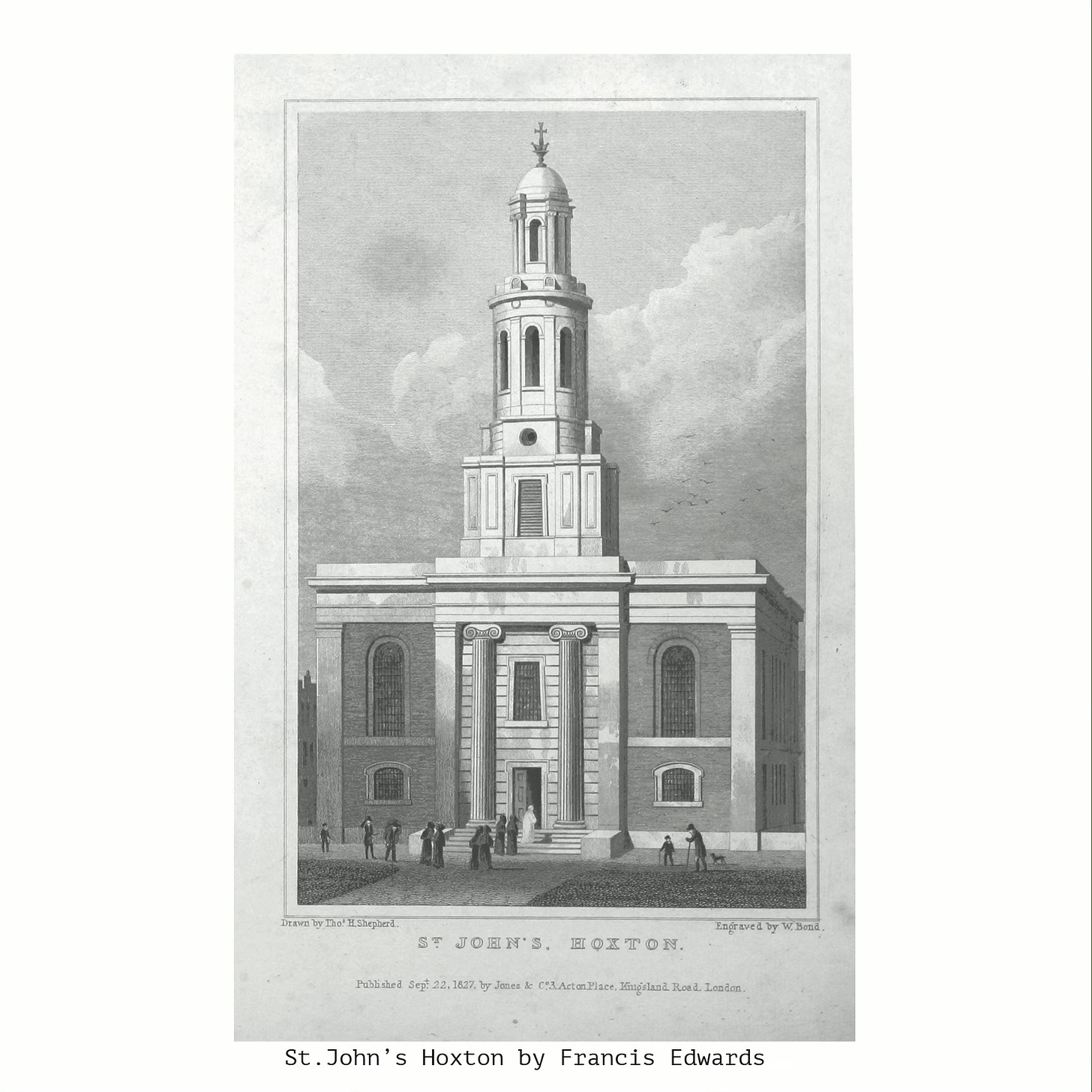

St John the Baptist Church, Hoxton, is one of these ‘Commissioners’ churches’ built between 1824 and 1826, designed by architect Francis Edwards (1784-1857) for the newly created Parish of Hoxton. The zeal for church building to serve the growing population continued for most of the 19th century. By 1896, Hoxton had been further subdivided into nine parishes, each with its dedicated parish church.

Edwards began his career in 1806 as an ‘improver’ in the office of the great London architect Sir John Soane. Two years later, he was admitted to the Royal Academy School and went on to be recognised as one of Soane’s most gifted students. Renderings from Soane’s office of Model Churches presented to the Church Commissioners bear a striking resemblance to Edwards’ design for St John’s. This may be due to the Commissioner’s strict design briefs. Edwards may also have participated in Soane’s Model Church designs or at least been influenced by them.

The drawings of Soane’s designs by J. M. Gandy show the churches as romantic ruins, alluding to the classical inspiration of the designs and suggesting that they might endure to become romantic archaeological ruins of a lost great civilisation.

Pesvner described St John’s as:

‘Unusually monumental for a Commissioners' church. Severe classical west front of three bays with two giant Ionic columns in antis and no pediment. The west tower appears above the broad parapet; it has a low square base, two circular, rather emaciated upper stages, and a stone cupola. The long sides of seven bays are all stock brick, with bays one and seven emphasised by giant Tuscan pilasters. Impressively wide interior; galleries on three sides, with curved corners, on Tuscan columns.’

After 200 years, the spiritual work of St John’s continues. Its website describes the church as ‘A Beacon Of Hope For Hoxton’. It may be for the churchgoing congregation participating in the diverse services and events performed beneath St. John’s stunning painted ceiling depicting the angels of the apocalypse.

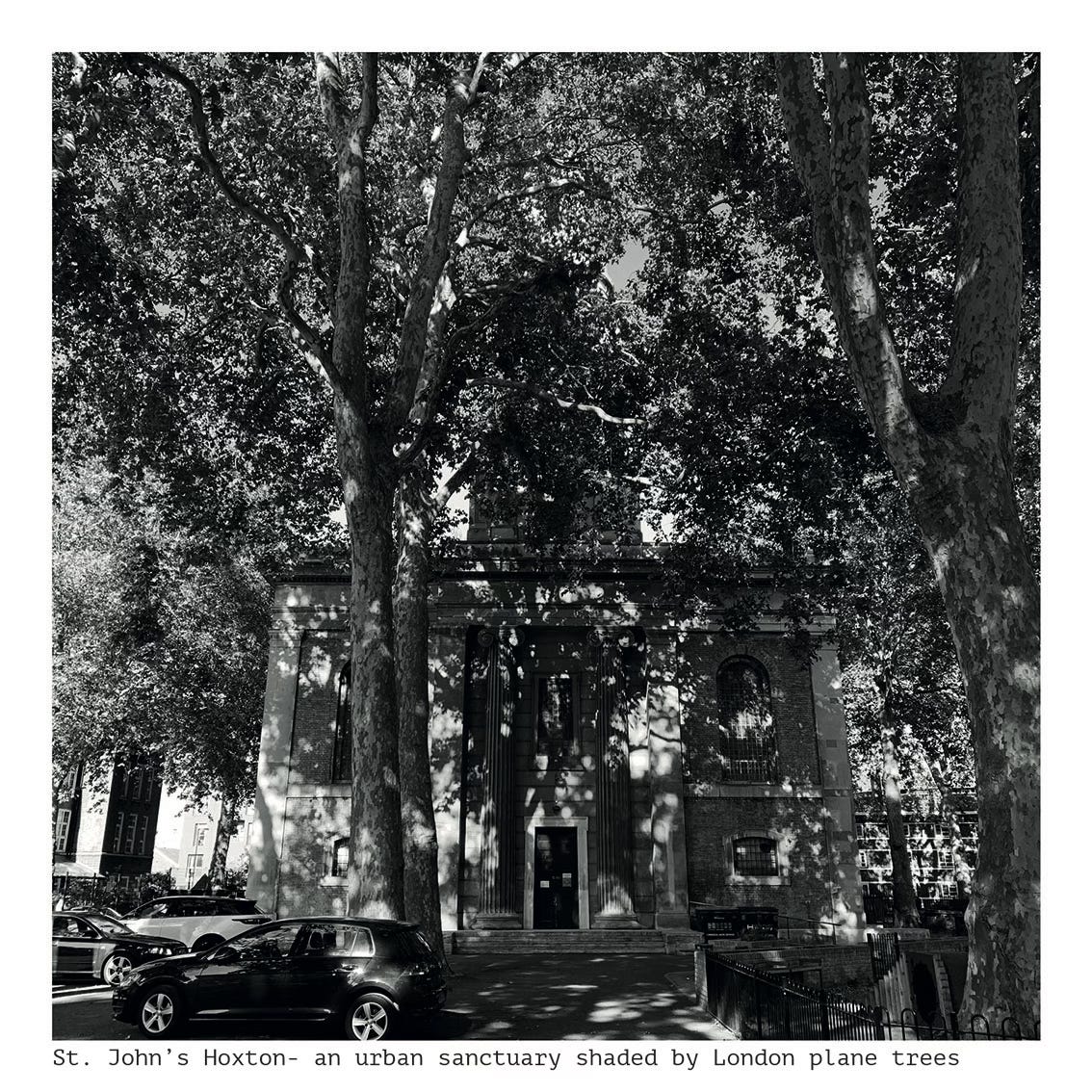

The graveyard setting for Edwards’ dignified model church provides a peaceful green sanctuary shaded by magnificent 200-year-old London plane trees, used daily for quiet contemplation and secular prayer.

Note. To read past Hoxton Chronicle posts, please subscribe to the free Substack Application and search for The Hoxton Chronicle.

Such an extraordinary concept to illustrate a building yet to be built as a decaying ruin…

Delightful glimpse of 200 years ago. How time flies in surprising directions