A photograph of a crowd gathered outside the Hoxton Cinema in Pitfield Street shows two large charabancs filled with men wearing caps, broad-brimmed hats and straw boaters. The cinema usher, dressed in a bright white coat and military cap, keeps order in the centre. In the foreground, a small group of poor, shoeless children scowl at the camera. Poster hoardings mounted on the ornate cinema front advertise the latest films. Above the cinema entrance is a cut-out figure of a tramp and a sign reading ‘I Am Here Today’. It is 1921, and world-famous film star Charlie Chaplin has returned home to the city he left just ten years before as a little-known member of the Karno Variety theatre troupe. Wherever he appeared, his progress was mobbed by adoring crowds like those in the photograph.

A closer study of the photograph raises questions and doubts about our interpretation. Why is the crowd gathering to meet Chaplin made up entirely of men? The posters advertise the film ‘Peace at any Price’, a romance and double-cross drama released in 1915 not 1921. Perhaps Charlie Chaplin was not there that day. History depends on the interpretation of the few objects, images and texts that endure over time, it is an art fuelled by doubt. We might be wrong, but it is a good story.

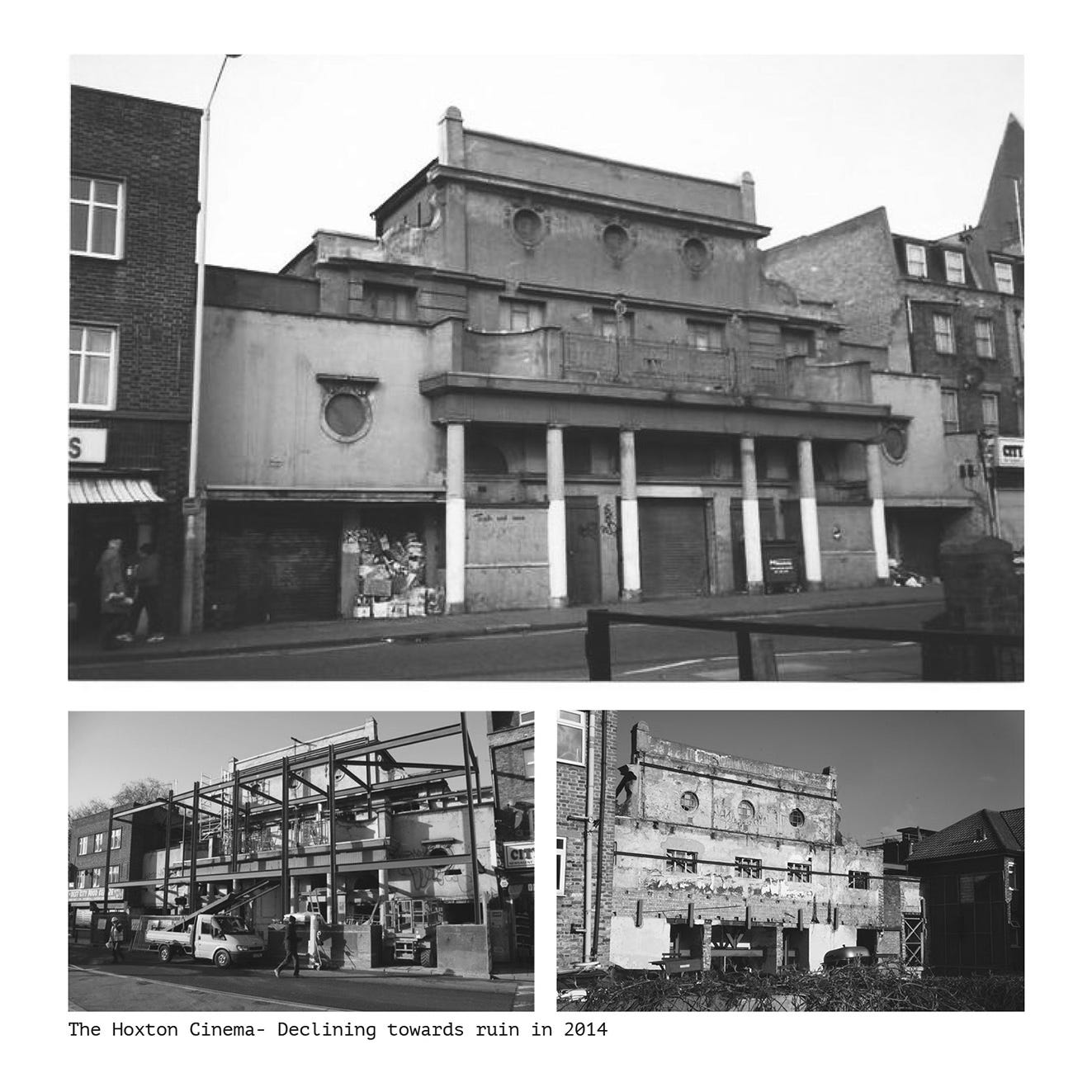

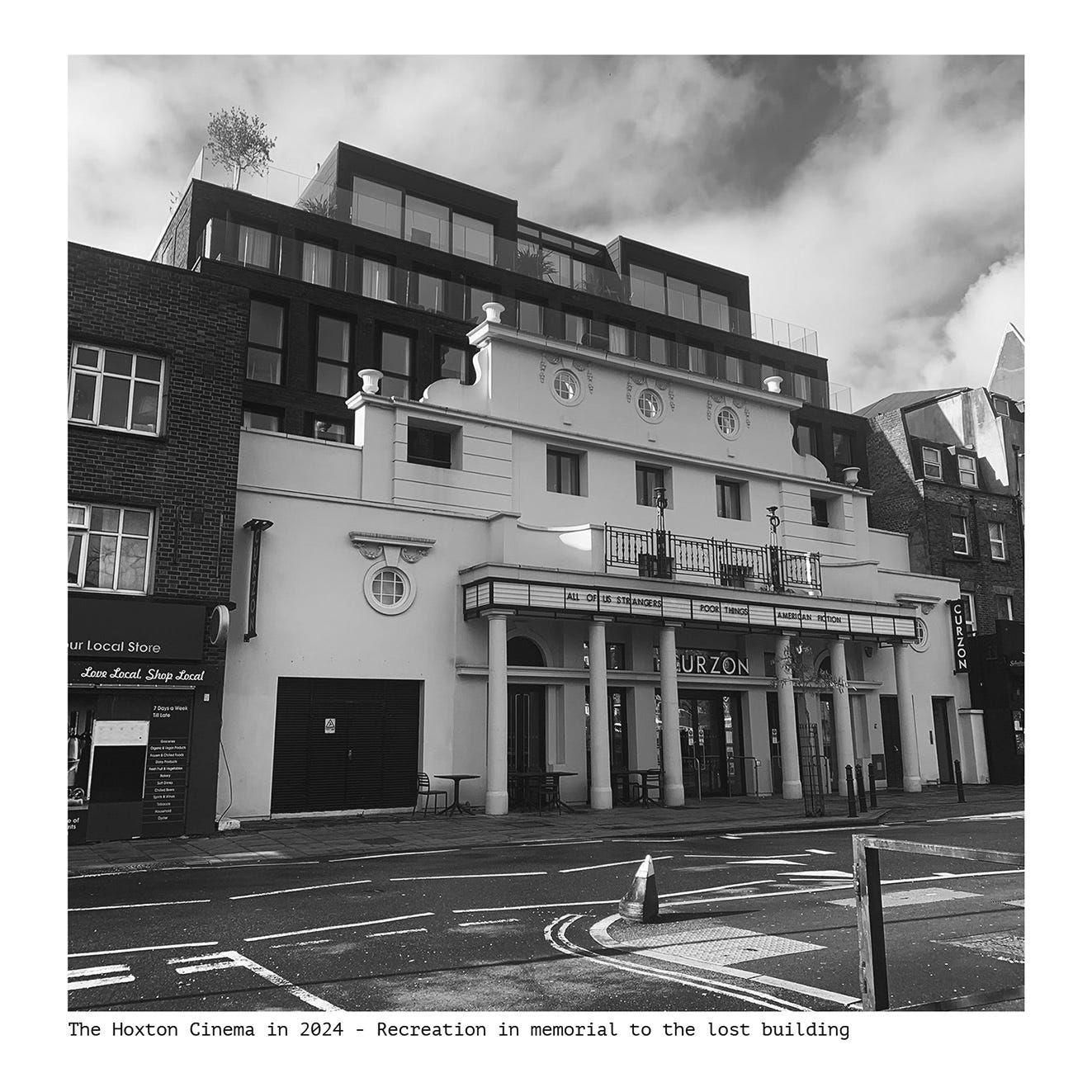

A century later, Hoxton Cinema still stands on the same site in Pitfield Street as shown in the photograph, but not in the same building. That original Hoxton Cinema closed decades ago. Most of it was demolished in 2014; however, the derelict street façade was retained, propped up by a framework of steel girders. When work began on the façade restoration, it was realised that the fragile old structure was beyond repair, so an approximate reproduction of the original was substituted for the restored original. Architects Waugh Thistleton designed the new building behind the facsimile of the original cinema facade. It includes a new foyer facing the street linked to the Hoxton Cinema, buried in a deep basement. A block of flats fills the space above the cinema.

The photograph reveals the fleeting nature of urban life, fixing forever a single moment in an image carried into the future. Incomplete references and unreliable memory ensure that we cannot be certain that what we think is happening in the photo is true. In the absence of research, we can only guess or invent appealing narratives that seem to fit with the evidence.

Buildings change more slowly than the events of daily life, providing an illusion of permanence, but architecture is also constantly changing as it decays towards ruin. For the first time in history, photography shows how little of the built city remains after a century of wear, decay and replacement. Old photographs like this one induce a nostalgic melancholy for what has gone.

Architectural conservation attempts to address this sense of loss, or at least to slow the process of urban entropy and erasure by retaining the best of what exists for the utility and delight of future generations. Of necessity, the process is highly selective. Taking the Hoxton Cinema as an example, nothing that appears in the photograph now remains. All the most emotionally engaging elements in the photo, the smiles, the people, the charabancs, the posters, are all long gone. What endures is a partial reproduction of elements of the old Hoxton Cinema acting as a sign directing our attention towards what might have been.

Seen in this way, conservation can be understood as the creative work of selective fiction piecing together fragments from the past to support a historical narrative. As this example demonstrates, the selection may even include approximate facsimiles of historic objects to communicate versions of historical truths.

Note. If you would like to read past Hoxton Chronicle posts, please subscribe to the free Substack Application and search for The Hoxton Chronicle.

Wonderful, another Friday night by the fire remembering the creative work of selective fiction piecing together fragments from the past to support a historical narrative.