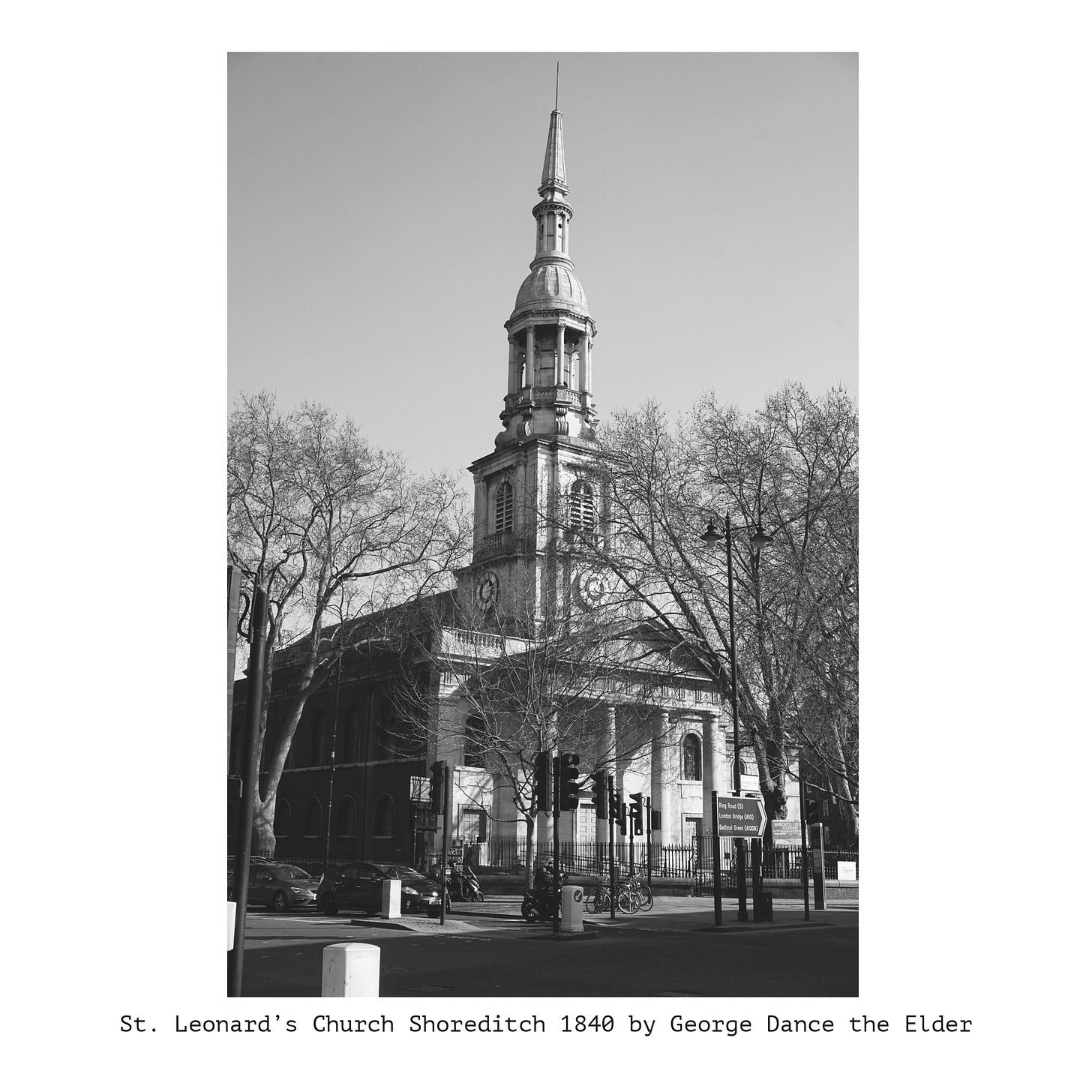

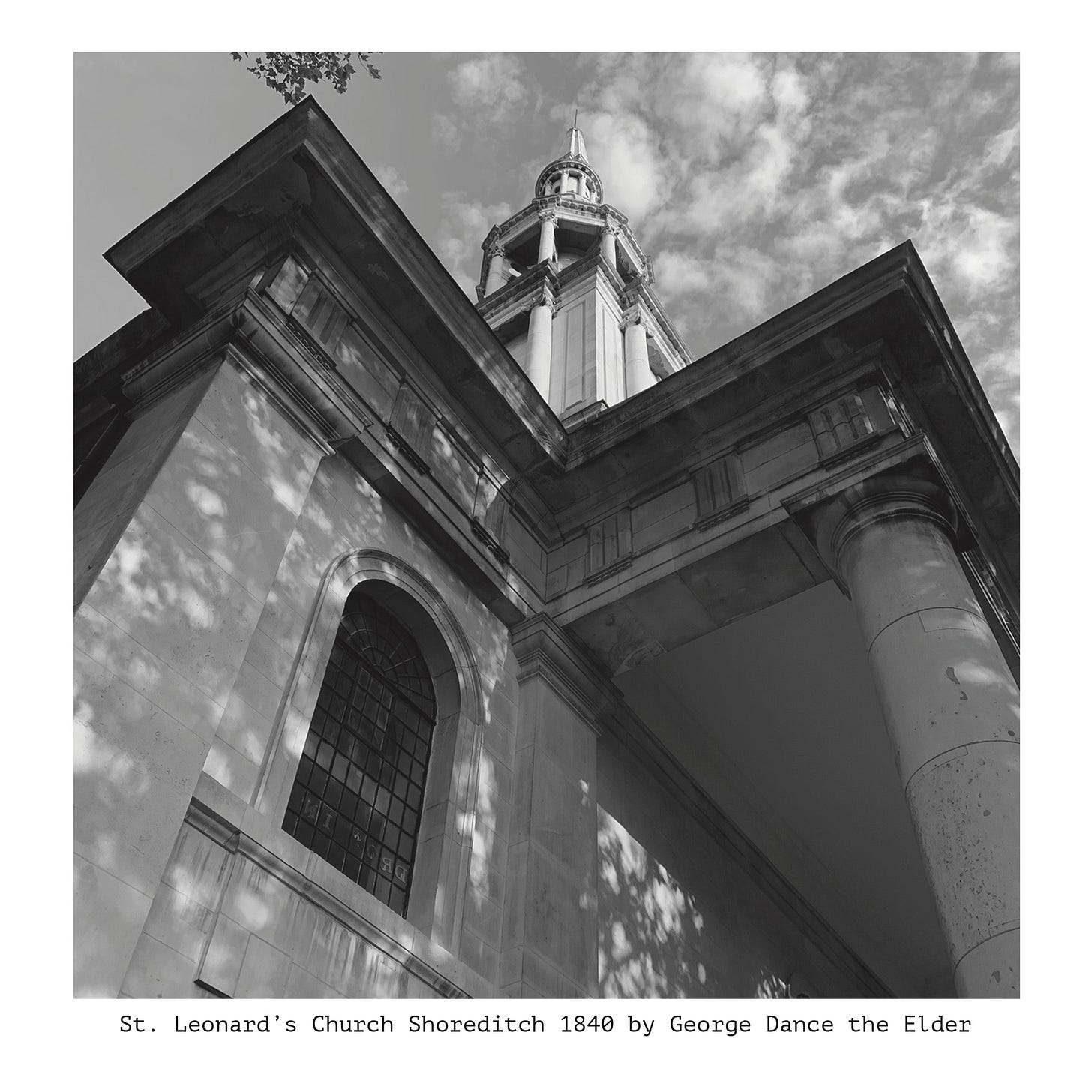

The Hoxton Chronicle. 057 St. Leonard's Shoreditch.

St Leonards Churchyard has been the burial ground for Shoreditch since at least the 12th century. By the mid-19th century, the needs of the growing metropolitan population for new burial sites had completely overwhelmed the Churchyard’s capacity. The 1852 Burial Acts were enacted to address the toxic public health issues that resulted from this shortfall. The act led to the establishment of Burial Boards, which raised funds to establish the many great Victorian Metropolitan cemeteries away from congested churchyards. Since St Leonard’s churchyard has ceased to be an active burial ground, it has gradually evolved into a scruffy, much-loved urban garden shaded by ancient London Plane Trees. It is a sanctuary for quiet contemplation, for chatting with friends, for lovers’ assignations, and for the lonely, troubled, and homeless. The churchyard is managed in an ad hoc way by volunteers. Among overgrown planting beds, there are benches and tables made from old pallets and scrap timber.

The newest memorial commemorates the dead from the First and Second World Wars of the 20th century. Older gravestones have almost all been removed from their original graves and now stand against the church walls. Rain and frosts have gradually eaten away at the stones making inscriptions and dedications barely legible. Nature orchestrates a gentle, slow process of forgetting that cannot be hurried.

John Stow, writing in the late sixteenth century, relates the story of one of St Leonard’s vicars who was keen to accelerate the process for his profit.

‘Notwithstanding that, of late one vicar, for the covetousness of the brass, which he converted into coined silver, plucked up many plates fixed on the graves, and left no memory of such as been buried under them, a great injury both to the living and the dead, forbidden by public proclamation, in the reign of our sovereign lady Queen Elizabeth, but not forborne by many, that either of a preposterous zeal or of a greedy mind spare not to satisfy themselves by so wicked a means.’

Standing next to the great portico of St Leonards are the rusted remains of a water pump dating from 1832, twelve years older than the current church. It must once have provided water for the local community in the days before mains water became available during the latter half of the 19th century. The pump handle is missing, the octagonal central pillar is cracked, and the heraldic crests on each face are almost illegible, filled with countless layers of thick black paint. A graveyard seems an unsuitable location for a drinking water pump, however, we moderns neglect the purifying force of sacred places believed in by our forebears. It is also likely that the churchyard has become the repository of odd fragments of redundant community infrastructure. For example, the Shoreditch Stocks are preserved in the church. It seems likely that the pump, when operational, stood in the street outside the graveyard.

St Leonards is the Parish Church of Shoreditch and was once a vital focus for the community as a place of worship, local administration, christenings, weddings and funerals, education, and care for the old and poor. Since about 1850, the utilitarian functions of the church have gradually been taken over by municipal borough authorities equipped with the necessary budgets and capacity to deliver the services needed in a great city.

The churchyard has become a retreat, seemingly detached from city concerns beneath the great church spire, pointing emphatically towards heaven.