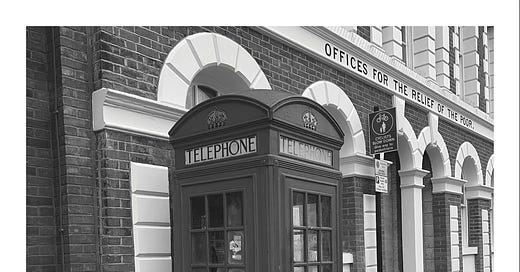

I was surprised and delighted to recently discover a classic red British telephone box standing in Hoxton Market in front of the recently restored façade of the Offices For the Relief of the Poor that was originally part of the Hoxton Workhouse.

The telephone box is an example of a utility originally intended to provide private connections between individual houses and businesses, transforming to become a public utility shared by all. The transfer of services between private facilities and public utilities is a constantly evolving aspect of the city making process. The phone has recently changed once again to become a private facility now enhanced with vastly increased technical capabilities. After a century of life on the street the public telephone box is becoming a rare sight. Soon they will exist only in museums and in themed interiors. Sadly, but perhaps inevitably, the public telephone in the Hoxton Market does not function.

It is now difficult to imagine quite how disconnected people were from one another before the age of the telephone. In those times (not so long ago) meeting was by chance or else prearrangement well before the encounter. Discussion took place face to face. Communication at a distance was only possible by letter or, for urgent messages, by telegram relayed by the Morse code.

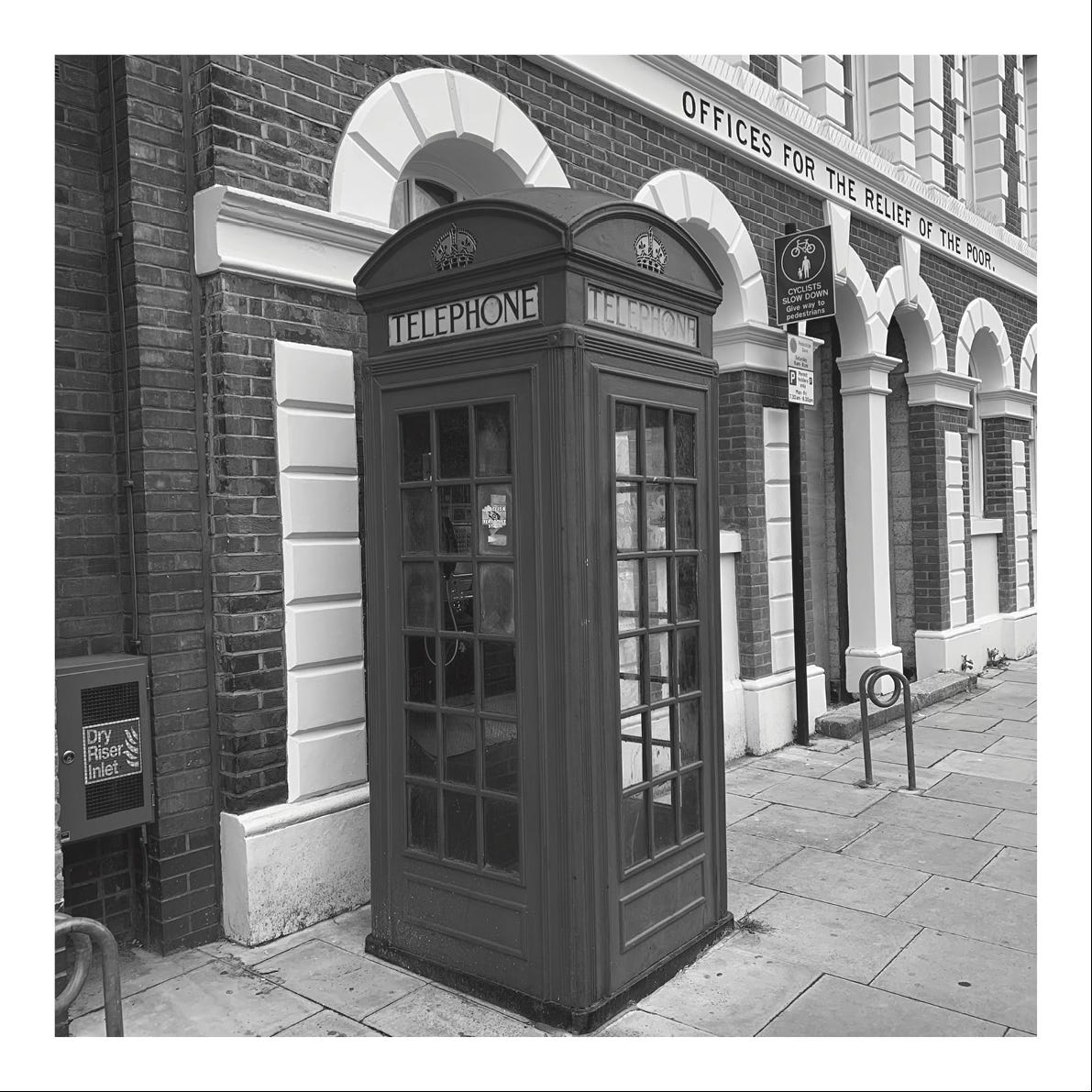

The General Post Office Telephone Kiosk number two (K2) was designed by architect Giles Gilbert Scott in 1924. The competition for the design was promoted by the Royal Fine Arts Commission in response to widespread dislike of the earlier K1 design made in concrete. It is interesting to speculate why an architect of Scott’s eminence, busy with the construction of Liverpool Cathedral, would be interested to participate in the design of a humble kiosk. Perhaps he understood how the installation of many tens of thousands of these kiosks across cities and villages of Britain, and parts of the British Empire, would change the world. For the first time in history anyone could converse directly with anyone else regardless of distance. This revolutionary innovation must have seemed miraculous. Whatever his reasons were, he stayed with the project and was engaged to prepare several variations to his original design over the following decades.

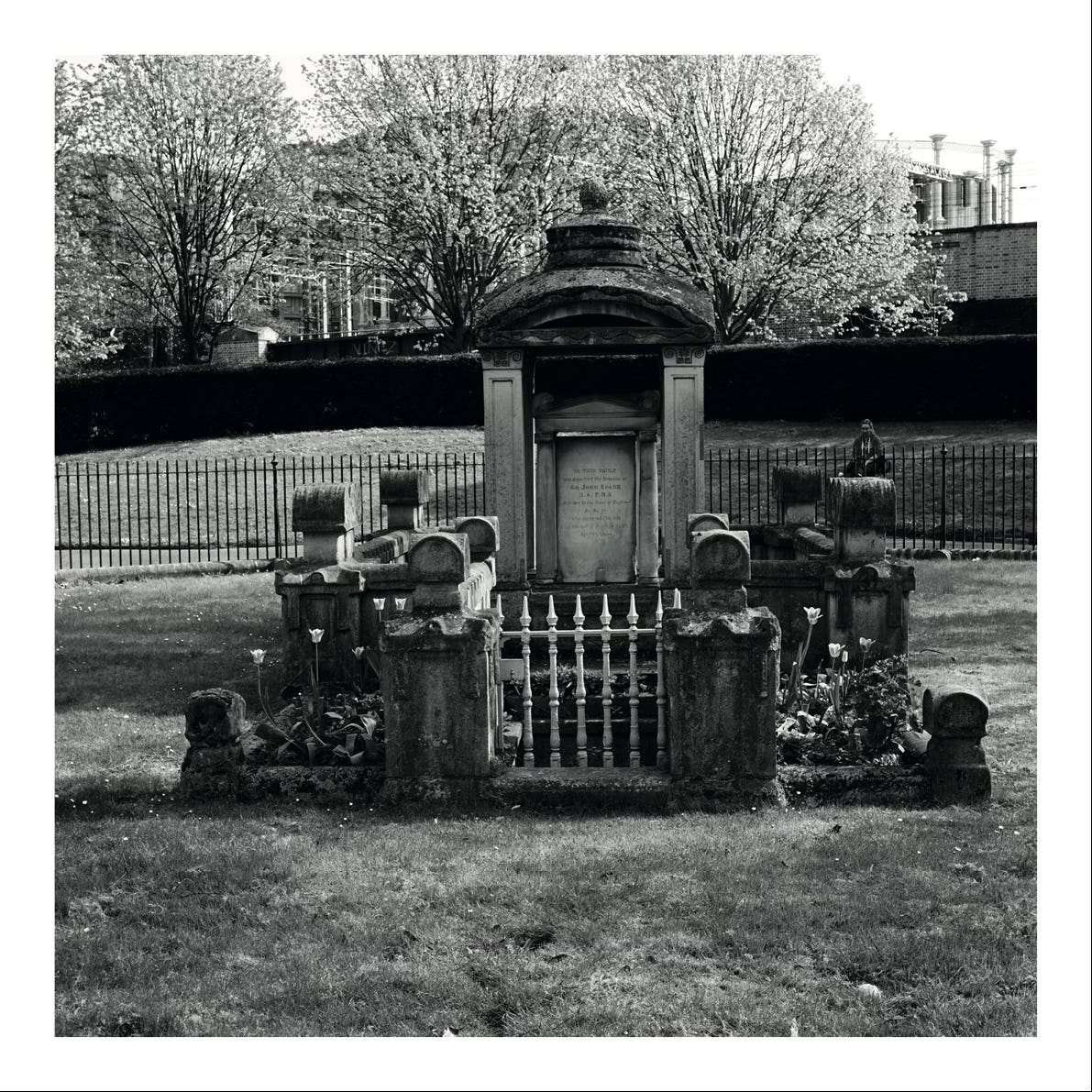

Scott was a trustee of the Sir John Soane Museum the former home this great British architect who died in 1837. It is possible that the inspiration for K2 arose from Scott’s familiarity with Soane’s work. There is, for example, a striking resemblance between the K2 design and the entrance pavilion to Soane’s family mausoleum that he designed and built in St Pancras Church yard. The K2 roof of a circular dome fitted onto a square base is also a frequent motif in Soane’s work. However, Scott’s design may have resulted from a careful analysis of function and developed from first principles. The truncated dome roof may be just a neat way to shed rainwater in the right places. Creative inspiration is never direct or simple.

The K2 telephone kiosk, and the modified designs that followed, were made in many different locations from cast iron. The choice of material following a tradition of making robust cast iron post boxes able to withstand punishing conditions outdoors in all weathers. A sign on the back of the one in Hoxton Market, encrusted with many layers of paint, confirms that this one was cast by the W Macfarlane and Co Saracen Foundry in Glasgow at some time before 1965 when the works closed.

In Pitfield Street there are two more recently designed telephone boxes.

The first is a KX100 telephone kiosk designed in 1985 for newly privatised British Telecom by the manufacturer GKN (the former Guest Keen and Nettlefolds). BT’s original intention was to replace all the old red boxes with these new hi-tec alternatives. Thankfully, in the face of public outcry, they failed to deliver their plan. The clean lines polished stainless steel and glass of the KX100 do not respond well to neglect and dirt. Hi-tec does not mellow as it decays to ruin.

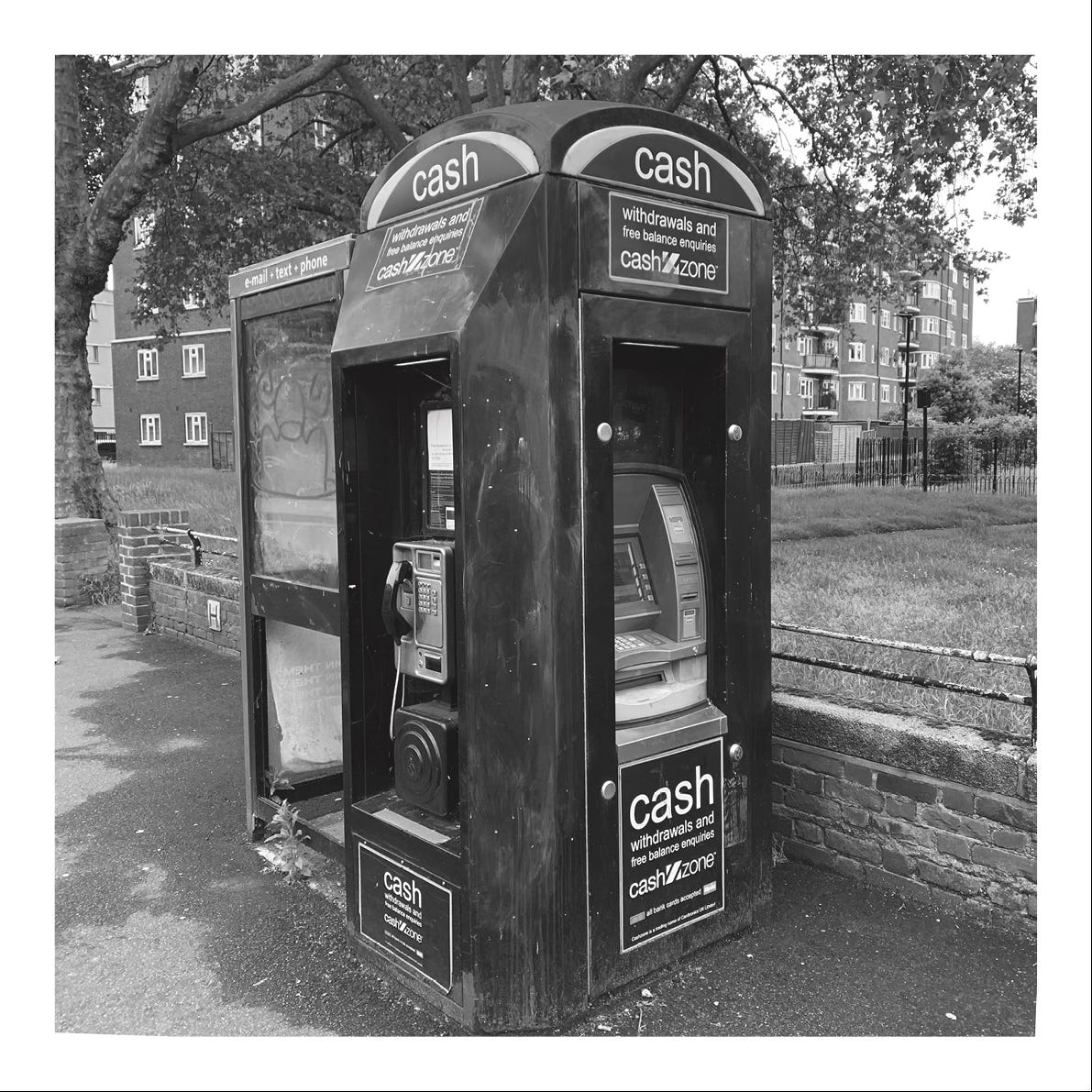

Next to the KX100 is a strange hybrid piece of street infrastructure that serves as a combined cashpoint, phone kiosk and Wi-Fi hot spot. It is a similar size to the Gilbert Scott classic and retains the same roof form. To unify the disparate parts of this clumsy assembly the entire structure is painted all over in charmless black paint.

Cash and public telephones are rapidly disappearing from public space as they merge to become a composite utility deliver to every individual and business through an invisible network of virtual connections. Soon the imposing architecture of buildings and familiar street kiosks that formerly provided these services will be gone and largely forgotten.

The restless process of constant urban change rolls onwards with wireless technology and virtual services displacing the need for architecture.

Wonderful! I have seen some traditional

telephone boxes repurposed as mini-libraries. They are an iconic piece of street furniture and distinctly British. Long live the red phone box!

A really interesting piece, thank you