The Hoxton Chronicle. 026 - The Haberdasher Estate.

The 1945 County of London Plan for the post war reconstruction of London identified houses in Buttesland Street and Chart Street, Hoxton as slums. By 1967 the entire area had been cleared and replaced by the Haberdasher Estate designed by Stock Page and Stock for Hackney Council.

Before the slum clearance 131 terraced houses with small back yards lined these streets served by four corner pubs with workshop buildings tucked into the centre of the urban blocks behind the houses.

The slum designation suggests that these houses were shoddily built and poorly maintained with inadequate access to services of all kinds. The designation of slums was incorrect in one sense. These rundown houses were built on clearly defined land plots with secure ownership title facing onto adequate streets. This was slum architecture within an ordered town planning regime of small building plots. In other words, it was a well-planned slum.

The commentary supporting the County of London Plan suggests that they were probably overcrowded with poor tenants crammed into every available space to keep a roof over the heads of extended families. The slums were privately owned and run by slum landlords extracting small rents from poor families. The condition was an expression of the market-based approach to housing catering for the very poorest Londoners. Elsewhere in the area, notably in adjacent Haberdasher Street, local authorities and charitable foundations had been working since the late 19th century to provide charitable housing of many kinds. These most welcome additions to the housing stock were reserved for ‘the deserving poor’ and were generally more expensive to rent than the slums they replaced. The slum marketplace provided the only available meagre shelter for London’s poorest.

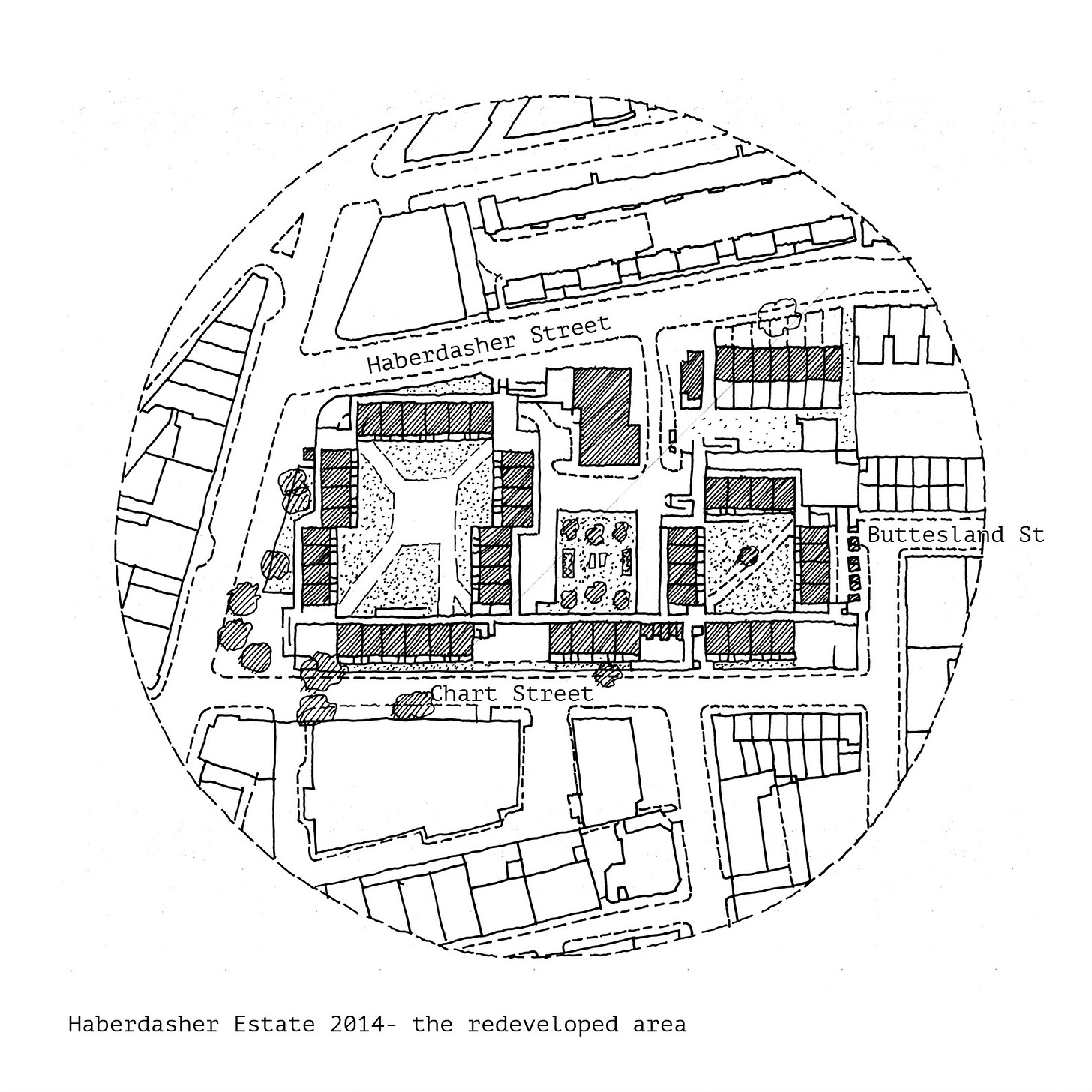

The new Haberdasher Estate replaced 131 houses with 7 houses, 48 two-story ‘maisonettes’,58 flats in low level terraces, a 16-storey tower of 64 fats, and extensive garage parking arranged around three courtyards. Providing a total of 178 ‘housing units’, an increase of 47 over what had previously existed. Private open space was limited to small terraces and balconies. The entire site was excavated by a half level below ground with the lowest level of accommodation raised half a level above ground. This strategy freed up the excavated level for traffic and car parking. Buttesland Street was erased by the development creating an inward-looking estate disconnected in plan and by level from the surrounding public streets.

The slum building plots were replaced with 8 house plots and a single giant interconnected urban block covering the remainder of the site. The small plot planning of the slums could have allowed for incremental changes to be made to each house including complete rebuilding if required. The giant block planning of the redeveloped estate makes incremental change and adaptation almost impossible. Each part of the estate is interconnected with, and depends on, its neighbour even for basic access. The slum would have allowed for change over time and the process of, what Jane Jacobs called, ‘un-slumming. The big plot estate planning has stopped this type of incremental urban change dead. Future changes will require a further round of wholesale redevelopment of the entire site along with all the associated costs, social upheaval, material and environmental damage of this type of change.

So, who benefitted from this compassionate municipal effort of slum clearance?

The 1945 plan was based on census data collected in 1938 so was already out of date when the plan was published. Action to replace the slums began in the mid 1960’s, twenty years later. In the interim period, between slum diagnosis and slum remedy, all the slum inhabitants will have aged. Many may have died. Children will have grown up and moved elsewhere. Some will have prospered and found better accommodation while others may have hung on awaiting rehousing. All would have had to move elsewhere to allow the plan to be implemented. How many would have then moved back? The dynamic nature of urban change dictates that with this type of big project planning few, if any, of the original slum residents would have ended up housed in the new Haberdasher Estate. Meanwhile the slum landlords will have been compensated for their loss in the compulsory purchase process and the participants in the development industry will all have made their fair return on investment and effort.

The error of this type of urban planning is that it conceives of the city as something fixed and simple. The reality is that cities are systems of complex order in a constant state of flux and change responding to the needs of ephemeral lives lived out within the buildings and spaces. With this understanding of the city, rather than the modernist planning dogma prevalent at the time, what other remedies could have been applied to the problems identified?

According to estate agent websites the few remaining early 19th century houses on Buttesland Street that escaped the planners wrecking ball have been patched and repaired many times over. They now sell for £1.25m.